DOJO KUN

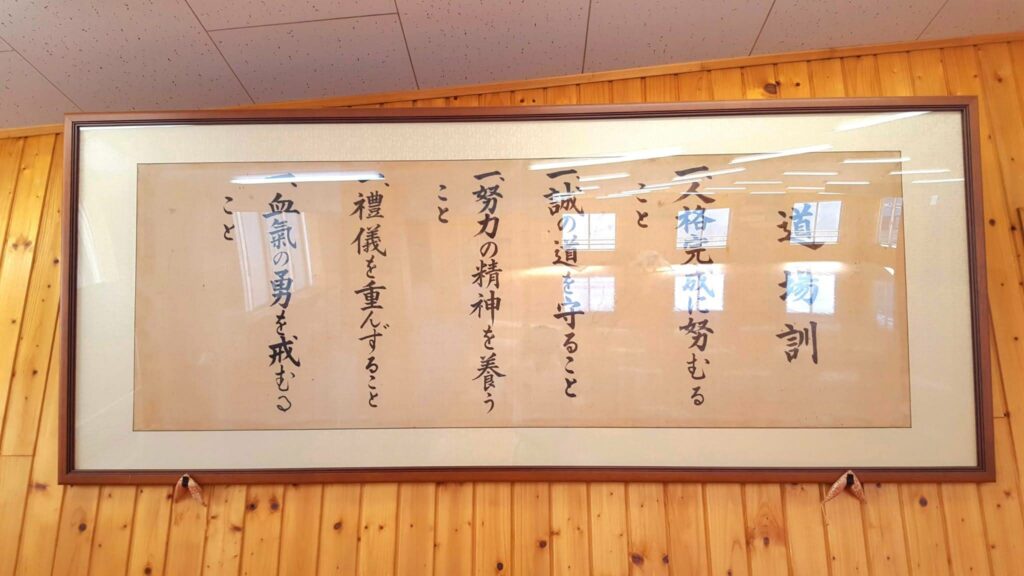

Dojo Kun at JKA Headquarters, Tokyo

The word “Dojo” means place of the ‘Path’ and “Kun” mean principles, so Dojo Kun are the guiding principles for the Dojo training place. In JKA there are the five guiding principles. Each principle starts with “hitotsu”, which means one/first, to emphasise that each one is equally important.

These are the main purpose of Budo Karate: to help everyone to become a Better Person.

一、人格 完成に 努める こと

Hitotsu! Jinkaku kansei ni tsutomuru koto

Exert yourself in the perfection of character

一、誠の道を守ること

Hitotsu! Makoto no michi wo mamoru koto

Be faithful and sincere

一、努力の精神を養うこと

Hitotsu! Doryoku no seishin wo yashinau koto

Cultivate the spirit of perseverance (put maximum effort into everything you do)

一、礼儀を重んずること

Hitotsu! Reigi wo omonzuru koto

Respect propriety

一、血気の勇を戒むること

Hitotsu! Kekki no yuu wo imashimuru koto

Refrain from impetuous and violent behaviour

After each training session, students kneel in seiza and recite these five precepts aloud, reminding them of the right attitude and virtues to strive for both inside and outside the dojo. This tradition, deeply rooted in Japanese martial arts culture, instills discipline, promotes unity, honors tradition, and integrates important philosophical principles of martial arts that create a peaceful society.

THE TWENTY PRECEPTS OF KARATE

Before establishing the JKA, Master Funakoshi Gichin outlined the Twenty Precepts of Karate, which serve as the foundation of the art. Rooted in Bushido and Zen principles, these precepts embody the philosophical core of the JKA.

- Never forget: karate begins with rei and ends with rei (Rei means courtesy or respect, and is represented in karate by bowing)

- There is no first attack in karate

- Karate supports righteousness

- First understand yourself, then understand others

- The art of developing the mind is more important than the art of applying technique

- The mind needs to be freed

- Trouble is born of negligence

- Do not think karate belongs only in the dojo

- Karate training requires a lifetime

- Transform everything into karate; therein lies its exquisiteness

- Genuine karate is like hot water; it cools down if you do not keep on heating it

- Do not think of winning; you must think of not losing

- Transform yourself according to the opponent

- The outcome of the fight depends on one’s control

- Imagine one’s arms and legs as swords

- Once you leave the shelter of home, there are a million enemies

- Postures are for the beginner; later they are natural positions

- Do the kata correctly; the real fight is a different matter

- Do not forget control of the dynamics of power, the elasticity of the body and the speed of the technique

- Always be good at the application of everything that you have learned.

BUSHIDO

Bushido holds significant importance for individuals practicing any form of ‘Do’, as it is the epitome of Japanese culture. However, its principles are also universally important since it can shape better the way we think and behave in today’s society.

Bushido is a Japanese term that translates to “the way of the warrior.” It served as a moral and ethical code that guided the Samurai warriors in feudal Japan; dictating how they should conduct themselves in various aspects of life, including warfare, politics, and personal behavior.

Written documentation about the code of conduct began to emerge more prominently during the Edo period (1603–1868). However, formal written works discussing Bushido as a distinct concept began to gain traction in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the modernization of Japan and increased interest in traditional Japanese culture. Nitobe Inazō‘s book “Bushido: The Soul of Japan,” published in 1900, is often credited with introducing Bushido to the wider Western audience.

The 7 principles of Bushido:

- Seigi: Righteousness, justice, correctness, doing what is right even in the face of adversity.

- Yuki: Bravery, having the courage to face fear with respect and intelligence so that one can live freely.

- Jin: Compassion, kindness, and empathy. Samurai looked strong on the outside, but they also believed in being strong on the inside through kindness and compassion, even after victory; not feeling glad/happy with someone else’s suffering.Reigi: Demonstrating courtesy, respect and etiquette. Samurai believed that people must admire them not only because they were physically strong but also because their behaviour had to show that they were very good persons. Not being cruel even to enemies, showing compassion. The difference between Jin and Reigi is that Jin is the compassion one feels inside, that others cannot see, whilst Reigi is what others can see from one’s behaviour.

- Meiyo: is crucial for Japanese culture, but also important for everyone. It means striving to be the best person you can be. By acting honorably and responsibly, you uphold your integrity, reputation, and dignity, taking full responsibility for all your actions.

- Makoto: Being honest, truthful, and sincere in one’s words and actions. Words must align with actions since they are considered the same. So you must be honest to yourself and also to the other people whilst also being kind and considerate in how words / actions will affect others.

- Chuugi: loyalty. Samurai chose to remain faithful and devoted to one’s lord, master, or cause, even at the cost of personal sacrifice. A choice to be loyal is not imposed, but the person himself decides to be loyal.

Since Bushido was deeply ingrained in Samurai culture, it heavily influenced various aspects of Japanese society including Japanese literature, philosophy, and martial arts. And while the Samurai class no longer exists, the ideals of Bushido continue to resonate in modern Japan representing its enduring legacy of wisdom, understanding, and inner peaceful strength, which Karate imparts to practitioners worldwide.

SHOUGAI KARATE

JKA Karate, is “Shougai Karate”, which means “lifelong karate”. It embodies the principle of lifelong pursuit and continuous improvement. In this approach, training is not seen as a finite goal but rather as an ongoing journey of refinement and mastery. One of the hallmarks of JKA Karate is the emphasis on constant repetitive practice of fundamental techniques through which practitioners strive to refine every detail of a technique.

This dedication to constant improvement makes JKA Karate well-suited for individuals of all ages and stages of life. Whether a child just starting out or an elderly practitioner looking to maintain physical fitness and mental acuity, JKA Karate offers a practice that can be adapted to one’s needs and abilities.

The philosophy of Shougai Karate emphasizes the idea that karate is not just a physical activity but also a path to personal growth and self-discovery. Through diligent practice and unwavering dedication, practitioners of JKA Karate can cultivate not only physical strength and skill but also mental resilience, discipline, and inner peace.

In this way, JKA Karate transcends the boundaries of age and physical capability, offering a lifelong pursuit that enriches the mind, body, and spirit.

JKA IS BUDO KARATE. What is BUDO?

“Budō (武道),” encompasses a range of traditional Japanese Martial Arts disciplines, which aim not only to teach physical techniques but also incorporate ethical, and philosophical aspects to become a Way of Life for the individual. The word Budō translates to “martial Way” in Japanese, Dō standing for ‘the Path’ that never ends, signifying a lifetime of dedicated practice to seek perfection of one’s character.

Budō, is not about Winning or Losing but about self-improvement, discipline, and personal development, going beyond mere combat skills.

There are several interesting and complex Budō concepts that are integral to the art of Budō Karate, which merge “tangible” body mechanics with the “intangible” mind and heart dynamics.

These are discussed in a series of interviews with Naka Sensei about Budō concepts

Inyo/ kyojitsu 陰陽/ 虚実: in oriental concept everything including bujutsu consists of inyo / yin yang, which means that even basic bujutsu movements have in-yo elements within. Our body control is naturally based on In-yo, such as power dynamics, balance between extensor and flexor muscles. In short all movements are embodiment of in-yo. In and Yo, opposite natures need to be employed in your movements accordingly. However, they are not to be separated. As ultimately they do not have a boundary to be differentiated from one another. And that is the difficult part. There is In-Yo in all that exists and Bujutsu is no exception. Reaching and withdrawing, contrasts/dynamics, switching dominant sides, everything is In-Yo. Go-Ju (hard soft) concept is the same. The hardness at its extremity turns into softness and vice versa. In other words, what you cannot physically see is Kyo (intangible) and what you can see is Jitsu (tangible). Again that is all within the concept of In-Yo. For example, simply put, in a state of jitsu one will be filled with energy and high spirit, while in a state of Kyo one’s energy is drained, spirit breaks, and even will to fight starts fading away. That is Kyo-Jitsu in Bujutsu. The question is how do you move between and deal with Jitsu and Kyo? If I am in the state of jitsu my opponent will sense my actions, so, I would put myself in a state of Kyo and use jitsu within the Kyo. For instance, imagine a water balloon. If you squeeze one side, the water moves to the other side. Likewise, In-yo are one side inseparable. You cannot split it. And as within one, the more jitsu there is, the less Kyo there will be and vice versa. So you need to strike a balance to be in control. Physical control can be practiced through power dynamics, switching dominant sides, balancing extensor and flexor etc. And then start dealing with the mind/spiritual side of Kyo-jitsu control when you actually face your opponent. Ultimately external and internal skills need to integrate into one.

Q: How would you explain the concept of void space emptiness empty?

Ku: I consider it synonymous with the concept of Mu (blank nothingness nonexistent nothing). Mu is more complex. So i use the concept ku to simplify. It is not to do so much with the concept of ku itself. It is more in line with what we talked about Kyo. When you put your body and/or mind in the state of Kyo (intangible), the concept of ku is simpler to grasp. Most people will think too hard trying to understand the concept of Mu as in mushin but find it easier when they are told to just “empty their mind”. And when they fight in that state, their opponent finds it harder to react to their movements.

Q: Does this mean your idea of ku and Mu are basically the same?

Philosophically different, i suppose but I regard the two as the same in this context, since we are talking about progressively guiding students into such movements. It is easier to get it right through the concept of ku. Like I mentioned earlier, rather than trying to completely eliminate the desire and will to beat your opponent, it is a lot simpler to try emptying your head. That way more of them seem to understand in their body. As though they can get the feel of the notion.

Q: So you use the concept of ku and Mu as a vehicle for teaching?

That’s right, as a means of guiding and instructing.

next theme is controlling Ma. Space time timing interval room. The culture of Japan is said to be a culture of Ma. The ma as in the slightest space between Kyo and jitsu (tangible and intangible). That is where your opponent cannot react. This must be hard to translate but in Japanese language we have a number of phrases with this particular word Ma to express a wide variety of states and phenomena. And as I mentioned earlier the Ma as in timings of body movements need to be controlled according to the situations with your opponent in front of you. Again Kyo and jitsu (tangible and intangible) come into the picture. You know ma also reads as “aida” (between). Though they are not completely separate from one another, when Kyo and jitsu switch from one to the other, there appears this slightest Ma, the space, the moment. That is where your opponent cannot react. So the question is how does one purposely create that Ma? It is extremely difficult.

Q: In English Ma-ai tends to be translated as distance.

Yes yes I am aware of that.

Q: My personal understanding would be “space-time”.

Yes, time and space = “space-time”.

Q: Which means controlling ma-ai is not about distance but space-time?

That is correct. In this context the space is not of a kind that you can measure in units such as centimetres. It is not a physical distance, but mental/psychological distance. And that is what you have to control, which is tough. Mental distance or more like psychological time. How do i put it? It goes “bang” to end but is beginning. Like, it is starting but has already ended. There I this indescribable Ma, you see? So at all time it is fresh. As though it is constantly being reborn. There are no divisions or separations. All connected in an invisible way.

I discover and realise something new everyday and get fascinated each time. At times i get torn between ideas. I’ve recently developed this feeling of having a sphere in front of me, so my movements have started flowing around the sphere. (Naka sensei showing flowing hand movements in tekki shodan). And my joints are beginning to move in a rounded manner. Intriguing isn’t it?

Q: Does it mean you have a guiding form to follow without thinking?

Yes, as though there is a ball right here.

Q: So your movements naturally happen along that form?

Yes I move along the outlines of the ball. That enables my movements to be clean and smooth. And stiffness and jerky edges are fading away. But then I discover some other way. And I constantly wonder which way to choose. Simultaneous discoveries of contrary ideas keep me contemplating. Q: Does it mean that conflicting ideas could be equally valid/ effective?

Yes, yes exactly, that’s what makes it constantly hard.

Q: What would be the idea in contrast to moving with a sphere?

Balance between extensor and flexor muscles.

Q: Do you mean more conscious use of body mechanics?

That’s right. From here (from technique 2 – 3 tekki shodan) if I move the sphere in front it goes like this, (brings hand close to the hikite hand and close to body then extends fast out again and pulled in to technique 3 fast) then this. Another way is striking a balance between extensor and flexor, when you pull with too much force you get stiff, so focus on the other side and deliver from the back, using the back extensor. Even this side (hand that is out) it’s not the hand that does the pulling but the back extensor. So I am using the extensor to pull from both sides. Using the muscles designed for extending to pull. Isn’t it curious? Various clues and ideas spring up at the same time. I don’t always know which one/s to go for. I get intrigued every single day though. Slowly like I said, imagine there is a ball in front of you (going through moves on tekki shodan) practice moving around along that shape. Do that a few times then try the other way. Like, try balancing out the extensor and flexor. I am not trying to decide which way is correct or better. Each way can be useful depending on the situation. You can set one as a theme to work on. As I always say, it is not just practicing kata, but practising with kata. And I wonder what will happen if I carry on pursuing both ways at the same time, whether they will merge and become one at some point. But then I discover something else on the way. So it I truly fascinating.

Q: So you as one person are somehow walking along two different paths?

That’s right.

Q: How fascinating!

Isn’t it? Yes this is really the way it is. One of the things that I have my focus on at the moment is study of body mechanics and practice in order to build physical ability. So it’s about body (tai) and techniques (waza). Then another thing is to make them workable and truly useful and practical. That will be yang (yo) also jitsu (tangible). This is how I think and practice. I am guessing all will eventually form into a single conclusion. Something new may come into being within me. All elements will dissolve and metamorphose. Balance between extensor and flexor muscles is in other words switching and dynamics of power, that’s yin and yang (in-yo). All is connected through the same system.

Q: you seem to be using different words to explain the One thing..

exactly! Here is an interesting and intelligible example. Let’s look at kyudo (Japanese archery). “Drawing” looks like “pulling” doesn’t it? You’d think they are using flexor muscles but actually they use extensor on their back. Though I looks like a pulling action, it is not. The extensor are doing the work. So I apply the same feeling to my movements (showing tekki shodan). I will show you. You will find this interesting. At first i was using my body this way, so with the flexors pulling my opponent towards me (ribbon around object on table holding two edges pulls towards him). But then I realised it is not a pulling force like this but an opening force on the back (pulls apart two edges and object is thrown towards him). It was an eye opening discovery. I used to focus on pulling this way, (grabs with both hands to pull) but I was wrong. I should be using the back extensor (arms pulled open). Fascinating isn’t it? Not pulling but opening. No focus on hands/arms but the back is moving forward and entering.

Q: So contradictions left unresolved may be making your journey even more interesting?

Yes. I’d rather let my body guide me to the answer. I find it more intriguing.

Q: What is the greatest inspiration for you?

There are great minds in any fields. I get inspired and stimulated by them all. It does not have to be budo, but different areas. Innovative people contributing to the society in diverse ways. They all bring inspirations.

Q: Regardless of the genres?

That is right regardless of the genres. They boost my motivation and will to go beyond my limits. And I wish to involve others around me on the way to aim and reach higher together.

Sport is based on a set environment and rules, then creating peak performance for a certain timing. In Budo, there is no set timing when you should build your peak to, that makes it truly “the way”. In a nutshell, sport is played in limited circumstances or rather fixed environments with certain rules. Within those frames one strives to reach their peak performance. Once you pass the peak and retire you’d coach the following generation without performing yourself. That will be one of the typical scenarios right? Whereas budo has no fixed rules, conditions or set timing when you should build your peak to, so I would say that makes it truly “the way”. It occurs naturally. You do not try paving a way yourself. It is naturally there. Therefore I keep walking on it. Winning or losing or a desire to break the record have gradually become irrelevant for me. Instead my focus has shifted onto my personal development. I wonder about those who walked on this path before me. What they have discovered and realised. What they felt along the way. I am interested in our predecessors’ experiences. Evidently by pursuing sports with Al one’s heart and dedication, one can nurture and develop a great personality. However, that is not a main purpose of sports. One might improve their personality as a result of pursuing a sport. In Budo, it is the other way round. The very first purpose is set to seek the perfection of character. At least in some cases. Unlike an unintentional achievement as a result. In Budo it is the starting point to strive to perfect one’s character. Another common process would be awareness arising through practice. One goes “wait a minute, this is not just a combat sport” “how come we have to pay AND clean the dojo?” howcome we have to treat Sensei either such reverence? But this Sensei has a gripping presence and he is strong. Though it is the primal principle in Budo, it is not easy to appreciate when you are young. Many go through a disorderly phase, then by looking after their disciples they themselves grow as well and realise it is important that they better their character. Otherwise one cannot lead others. When you are young, being crazy or eccentric may be part of your charm, but after all in order to lead many people, you will need to have a more noble kind of charm and higher moral standards, with compassion and tolerance. Through Budo practice this process of realisation naturally happens. I find it remarkable that this has been set firth as one of the main principles of Budo. Not a random consequence but the purpose guides you to be. And when you actually experience it you do understand. I now contemplate things that I had never imagined. Say, strength to be able to deal with anything. The idea/definition of being strong evolves as well. Strength and courage to withstand whatever hardships. Being strong in competitions does not mean much and is temporary, though its good on the spot. Or being strong as a Budo teacher in a dojo, is limited too. One should set an example with their attitude towards life, to be admired for their way of living, do that others wish to emulate and live up to the standards. That is the aim. To be such an example.

tell us about shizentai. The hardest state to achieve. The state that one can physically see, and that of one’s heart and mind. The two need to become one. Keeping it natural on the level that you can see is one thing. And then there is inside of the body, mind, heart. The external and internal states need to become one. Ki-gamae, kokoro-gamae, frame of mind, attitude. These elements are the foundation to begin with. And then they would gradually integrate with the external elements to become mu-gamae (no frame/ no guard). That I consider is shizentai, taking no particular stance at the ready. Mental readiness evolves into “no stance” so it eventually becomes formless. Even one’s mind loses its form. So one needs to truly know oneself in order to achieve inner shizentai? That is why I say it is the hardest state to acquire. Through Zen, Budo, Bujutsu, everyone is aspiring for it. Last remaining questions will be what is “mind?”, what is “heart”?, what is “life”? What is “death”? In search of the answer, some go through ascetic practices with strict disciplines to become gradually enlightened. Samurai had the same attitude. What was more important than technique was the introspections on the fear of death, contemplations on how and why the mind works the way it does, then elaborate further to probe what “mind” is in order to transit and step into the realm beyond. How should I put it? Religion that transcends religion, if you like. Not taught by others. Confucianism had significant influences upon philosophy of samurai? Yes, certainly, by learning such concepts from young age they might have found a way to conquer the fear of death. Still no one is thick enough to live without any inner conflicts. Teachings of Confucianism play relatively strong a role in political control? Yes, especially true for Neo-confuciansism. Along with then there lies Shinto of Japan and there is Japanese Buddhism. Each element contributed to form a unique ethos of Japan. Different from that of China or Korea. Based on the same Confucianism, their civil officers have higher positions than martial officers. Bushido = military officers are not respected in Japan it is the other way round. That is one difference. So it 8s not Confucianism, it is Bushi-Do. Evidently there is the essence of confucianism in it. The Interesting thing about Bushi-Do is that there is no scriptures or doctrines no guru or spiritual leader either. Who do you think one learns from? Their mother. Do not behave disgracefully, do not tell lies, do not bully the weak, their mother is the one who spends most time with them. No guru, no scriptures, no doctrines, instructions or orders. Each clan has its own ideology. Each family has its own ethos. Each era has its own ethics. However, they all share the same moral values as a human being. One should not lie. One should not bully the weak. Live gracefully. These are the ultimate points that had been strictly kept for many hundreds of years as the backbone of “Bushi”. While the concepts of loyalty and filial piety come from Confucianism. Similarly Shinto has no guru or scriptures either. That’s correct. Things that cannot be logically explained in words. For non-Japanese people this can come across as too ambiguous. Within that ambiguity lies an uncompromising core of virtues. That’s right. Most probably because of the mono-racial society. We can feel and read each others mind without depending on words. By living with one another, we get to know what others must feel. We have also been blessed with the wealth of nature here, with beautifully distinctive four seasons. Not being monotheistic must have been a factor as well. On each stone, river and tree reside it’s own spirits and god, Shinto deems. The Jomon period which lasted 10000 years must have formed the soul of Japan, before Confucianism, Buddhism and the likes came. But there was no formal acknowledgement as it was too natural to be noticed. Only when other cultural perspectives came, analysis on our own culture started. One can only self reflect when they have someone in comparison. Shizentai had literally been a natural state. Then intellectualisation was carried out later? We may be able to say that was “cutting-edge” culture. How we determine that now will be another matter though. Speaking of “cutting-edge” culture/technology, ancient stone fences made by just piling stones. Though they are known to be stronger than their modern counterparts, there is no way to quantify strength/unit. Construction regulation will classify them as not meeting the standards. However, modern and measurable methods have never achieved as much strength or stability. Fascinating isn’t it? That takes us back to our previous conversation about sport and Budo. I consider this another factor that forms the difference. In multiracial and multicultural society people rely on cleat pieces of information that are measurable and can be logically explained in words. The same system is applied to sports where everything has to be measured in numbers. How many metres you flew, how many seconds you took to run or swim, how many points you scored. Everything is converted into a numerical value. On the otherhand in Japan, we value things that cannot be physically seen. The intangible and unmeasurable, unspecifiable. The unmeasurable. For instance, in Sumo, one season consists of 15 days. Say, one wrestler wins all 15 matches, still no guarantee for him to be awarded the title of Yokozuna (the highest rank sumo wrestler). In the West if you win all the matches, no question whatsoever. You are a Grand Champion. In Japan winning matches alone will not determine the rank. General manners and behaviour. How you win, how you lose. The quality and way you fight. You ought to express everything in a match. Invisible quality, like one’s mind/heart. Mind cannot be physically seen but it flows out. That should be the focal point of evaluation. This concept must be foreign to Westerners. Vague and unclear they might say. Beauty of the undefinable, we Japanese find and we value those qualities. This must be hard to impart to non-Japanese people. But by sharing the knowledge like this, many Karate-ka will deepen their understanding. You know the book that I have written? Why don’t you translate it? Sure I will. For example, about Zanshin. As I constantly maintain, the beginning of the strike/technique is the end of the cycle. The end is the beginning. This concept represents everything including Hyori-Ittai (opposite sides of the same thing/phenomena). One, the same and inseparable. The end of one technique is the beginning of another. That obviously applies to body mechanics and mind mechanics as well. The sane goes for Zanshin. Then you go a step further to be ahead of time and the new era. In Western sport environment you KO your opponent and go “Yeah!” But in a real world you keep paying attention to prepare for the unknown to anticipate for what happens next. You wouldn’t be cheering after causing death with your sword. You wouldn’t fist pump for what you have done. You beg your victim’s pardon for carrying out your duty. You put your palms together after having to end someone’s life. That is the Japanese way.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN BUDO KARATE AND SPORT KARATE

Budō Karate and Sport Karate represent two distinct approaches within the realm of Karate practice.

Budō Karate emphasizes mental and spiritual growth alongside the physical techniques, promoting values such as respect and perseverance. It aims to integrate these principles into practitioners’ daily lives outside the dojo.

Unlike Sport Karate, which focuses on the younger generation, Budō Karate welcomes individuals of all ages and abilities, prioritizing dedication and personal growth. Members are valued for their commitment and attitude rather than their performance in competition.

“Emphasis on winning contests cannot help but alter the fundamental techniques a person uses and the practice he engages in. Not only that, it will result in a person’s being incapable of the unique characteristic of Karate-do. The man who begins jiyuu kumite prematurely – without having practiced fundamentals sufficiently – will soon be overtaken by the man who has trained in the basic techniques long and diligently.” Best Karate, Kumite 1, M. Nakayama

One of the defining characteristics of Budō Karate is the concept of progression at one’s own pace. Each practitioner is encouraged to develop and advance according to their individual abilities and goals. There is no peak to reach until one reaches a certain age.

Central to the philosophy of Budō Karate is the notion that the aim of training is not for competition. While Sport Karate may place a heavy emphasis on winning medals and trophies, Budō Karate places greater importance on the journey of self-discovery and self-improvement.

“The desire to win a contest is counterproductive, since it leads to a lack of seriousness in learning the fundamentals.… courtesy toward the opponent is forgotten, and this is of prime importance in any expression of karate” Best Karate, Kumite 1, M. Nakayama

Budō Karate values the intangible (invisible) characteristics of every person’s mind and heart. In fact, The first principle of the Dojo Kun : to “seek perfection of character” is the main purpose of Budo karate, encouraging people to cultivate a deeper understanding of themselves and their art through a lifelong pursuit of personal growth and fulfillment.